The Original Spa-Francorchamps: Where Racing Met the Edge

Forget the modern, sculpted track we see in Formula 1 today. The real Spa-Francorchamps, the one that lives in racing legend, was something else entirely. Picture this: a monstrous 14-kilometer loop of public roads, snaking through the misty Ardennes forests and villages. From the roaring 20s right through to the wild 70s, this place wasn’t just a circuit – it was a terrifying, beautiful beast that challenged drivers like nowhere else.

Speed Woven into the Hills

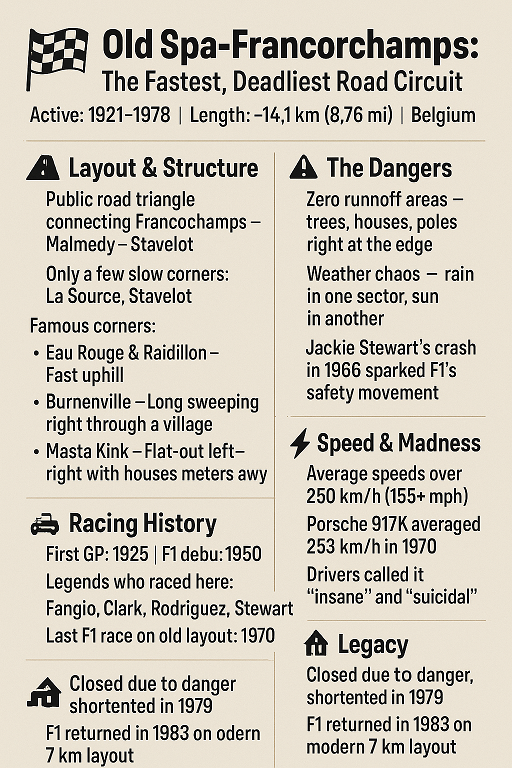

Born in 1921, the original Spa formed a triangle connecting Francorchamps, Malmedy, and Stavelot. It started with bikes, but Grand Prix cars soon arrived in 1925. Its soul? Pure, unadulterated speed. Imagine corner after corner taken flat-out, your foot barely lifting off the throttle. Only a few spots, like the tight La Source hairpin or the braking zone into Stavelot, offered a second to breathe.

Then, in 1939, they changed the game. They ripped out the Ancienne Douane hairpin and birthed the now-mythical Raidillon–Eau Rouge. Suddenly, that terrifying downhill plunge became an even wilder uphill battle – a blend of danger and pure adrenaline that still defines the track.

You’d blast out of La Source, plunge down towards Eau Rouge, then scream through Les Combes and Burnenville – a flat-out right-hander taken at insane speeds through the middle of a village. Next came the infamous Masta Kink. Imagine approaching a left-right flick at over 250 km/h (155 mph), with nothing but unforgiving brick walls, telegraph poles, and the sides of barns lining the road. One tiny mistake here? It wasn’t just a spin; it was disaster.

Beauty Masking Brutal Danger

Spa wasn’t just fast; it was deadly. Forget modern run-off areas. Here, ancient trees, stone farmhouses, wooden fences, and even streams sat right beside the tarmac. The Ardennes weather played cruel tricks too – rain could drench one section while sunshine baked another, catching out even the greatest drivers in an instant.

The cost was tragically high. The 50s, 60s, and 70s saw multiple drivers lose their lives. Stirling Moss had a horrific crash at Burnenville in 1960. That same, dark Belgian Grand Prix weekend claimed Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey. They tried adding chicanes and barriers later, but it was like putting bandaids on a gash. F1 drivers, fearing for their lives, started refusing to race there. By 1970, Formula 1 declared Spa too dangerous and left.

But the track wasn’t done. Sportscars and endurance monsters like the earth-shaking Porsche 917K kept racing until 1978. Drivers like Brian Redman called it “completely mad,” especially in cars averaging over 250 km/h for an entire lap. Madness indeed.

A Track Forged in Courage

Despite the fear, or perhaps because of it, the old Spa became hallowed ground. Legends like Fangio, Clark, Ickx, Rodriguez, and Stewart all wrestled with it. Many feared it as deeply as they loved it. Jackie Stewart, after a horrific 1966 crash left him trapped and injured for hours, became perhaps its most famous survivor and a leading voice demanding safety reforms in motorsport.

Winning at Spa wasn’t just about being the fastest. It demanded raw courage, unbreakable focus, and sheer survival instinct. A single lap was a tightrope walk between immortality and oblivion.

The Ghost That Still Whispers

In 1979, the beast was finally tamed. A shorter, safer layout was built, bypassing the lethal public road stretches. F1 returned to this new Spa in 1983, where it still thrills today.

But the ghost of the old Spa never left. Drive those Ardennes roads now, and you can still trace its bones. Cruise through Burnenville, blast down the Masta straight, or take the original Malmedy corner. The asphalt is quieter now, but if you listen closely, it still whispers tales of unimaginable bravery, blinding speed, and heartbreaking tragedy.

For those who know its story, the original Spa-Francorchamps stands as the ultimate monument to road racing’s golden – and most brutally dangerous – age. It wasn’t just a track; it was a crucible where courage was tested against the very limits of what machines and men could endure.